INTRODUCTION

It is classified as a vitamin, but in its activated form, vitamin D acts as a hormone whose function is to allow the intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphate. In theory, there is no need to introduce it into our diets because our bodies can synthesise it. However, in reality, for many different reasons the percentage of people who have a vitamin D deficiency is very high and constantly increasing.

Synthesis takes place in the skin and requires exposure to the sun. Vitamin D is produced from 7-dehydrocholesterol, which is converted into vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) when activated by UV rays. Vitamin D3 is the most active form in restoring levels of vitamin D in the blood and it can be ingested through diet in animal products or produced by our bodies through exposure to the sun. There is also vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) of vegetable origin but that has proved much less effective than D3 in preventing bone demineralisation and the risk of fractures.

Once vitamin D3 is inside our bodies, it must be activated by two hydroxylation steps before it can act on the target organs, particularly the bones. The first hydroxylation takes place in the liver by an enzyme called 25-hydroxylase and it is produced by a pre-vitamin D3, calcifediol. A second hydroxylation occurs in the kidney by the enzyme alpha hydroxylase. This produces calcitriol, which is the active form 1 alpha 25 dihydroxyvitamin D3.

So, if vitamin D is produced by our bodies, why is such a high percentage of people deficient in it? And why is this problem more prominent in people with Cystic Fibrosis?

Our lifestyles revolve increasingly around being in closed spaces with artificial light (schools, offices, etc.), exposing our skin to less and less sunlight, which is fundamental for the production of vitamin D. For individuals with Cystic Fibrosis, this is aggravated by the intestinal malabsorption of vitamin D through diet and potential complications of the disease, such as impaired liver and kidney function, which can contribute to a reduction in the activation of vitamin D.

THE ROLE OF VITAMIN D

It is interesting to explore more in detail why vitamin D is so important for the general population and even more for anyone who suffers from Cystic Fibrosis.

The importance of vitamin D for bone metabolism is well known. In order to avoid calcium deficiencies, calcium also needs to be introduced into the diet at an appropriate level, vitamin D synthesis and exposure to UV rays must be sufficient and the physiological processes in the liver and kidneys must work perfectly. It only takes one of these factors to be lacking for a patient to suffer from deficiencies.

The recent discovery of the presence of vitamin D receptors (VDR) outside the bone tissue shows that this vitamin is not only involved in bone metabolism but can also affect other organs and their functions, including respiratory and lung function, immunological processes and diabetes.

Finally, it is good to remember that a concentration of vitamin D in the blood ≥ 30 μg/L is considered normal and it is important to reach that level to prevent any negative consequence in health. Blood levels < 30 μg/L are considered insufficient.

HYPOVITAMINOSIS D IN CYSTIC FIBROSIS

Many patients with Cystic Fibrosis suffer from pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, which involves a high deficiency in the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins.

Adding fat-soluble vitamins to patients’ diet is fundamental and the Guidelines on this topic provide precise instructions on the appropriate daily intakes of vitamins A-D-E-K.

In the majority of cases, vitamin supplements can resolves deficiencies in vitamins A-E-K. However, deficiency in vitamin D is still high in a large percentage of people that regularly take vitamin D in the form of multivitamins formulated in accordance with the Guidelines.

There can be many different reasons for a vitamin D deficiency in patients with cystic fibrosis:

Literature on this topic states that around 90% of the population with Cystic Fibrosis is affected by hypovitaminosis D, a condition that can lead to a worse clinical outcome.

Vitamin D:

Data shows that patients with a higher concentration of vitamin D in their blood serum have a higher FEV1 and FVC than the group of patients with hypovitaminosis D.

Cystic Fibrosis related diabetes (CFRD) is another important complication affecting 50% of the adult Cystic Fibrosis population and vitamin D can help to prevent it.

In addition, vitamin D blood levels should be monitored in anyone having a lung transplant, which is often the last resort to prolong their life. Low levels of vitamin D in the blood can increase the probability of rejection because vitamin D effects the maturation and activity of T lymphocytes.

VITAMIN D SUPPLEMENTATION IN CYSTIC FIBROSIS

It has been proven that patients with Cystic Fibrosis have trouble absorbing high doses of vitamin D, despite the ingestion of pancreatic enzymes. They also have lower absorption than individuals without this disease and it has been proven that these patients have a reduced ability to convert ergocalciferol into the active form of vitamin D compared to control subjects.

The dietary supplementation of fat-soluble vitamins is an important recommendation for these patients.

The Guidelines suggest a daily supplementation of vitamin D between 400–2000 UI and generally this is enough to resolve the deficiency. However, monitoring blood levels has revealed that the majority of patients to do not manage to achieve the optimal levels described above.

For patients that do not achieve 30 μg/L of vitamin D through daily supplementation, it is advisable to increase supplementation of vitamin D further.

Some treatment schemes currently used suggest further intake of vitamin D in single doses once or twice weekly in high quantities. These are typically 12,000 UI/week for children and 50,000 UI/week for adults. Despite this additional supplementation, many patients still have hypovitaminosis D.

The need to reconsider this approach of administering high doses of vitamin D

in a single administration is also suggested by the results of a study conducted by the Johns Hopkins Cystic Fibrosis Center in Baltimore. In this study, patients’ vitamin D levels were evaluated and it emerged that around 81% of the patients had levels lower than 30 μg/L. Some of these patients agreed to follow a vitamin D supplementation course of 400,000 UI over 8 weeks (50,000 UI/week). At the end of the 8 weeks, only 8% of the patients had reached the desired level. Some of the patients that had not reached the levels expected decided to undertake a second round of treatment consisting of 800,000 UI over 8 weeks (100,000 UI/week) and none of these patients responded with a significant improvement in their vitamin D blood levels.

It is possible that for patients with Cystic Fibrosis, prolonged treatment with an average daily dose of 3,000–5,000 UI could be more effective.

Due to the growing evidence of the high number of patients that do not achieve the optimal levels of vitamin D in their blood, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation has issued a new series of recommendations on vitamin D supplementation.

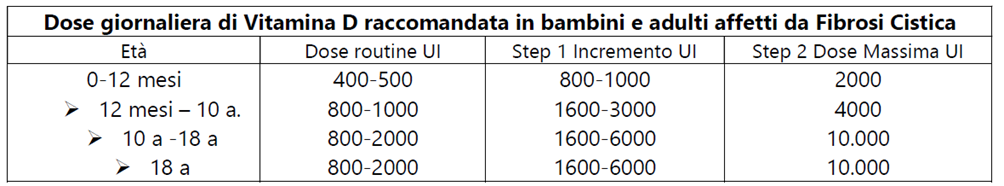

The table below shows the new incremental recommendations for vitamin D3 according to age.

(Ref.10)

(Ref.10)

The recommended dose has slightly increased and it is preferable to use vitamin D3 rather than D2, which is not absorbed as well.

Finally, it should be emphasised how intestinal absorption problems can aggravate hypovitaminosis D in these patients. The absorption of a film through the sublingual mucosa could partially overcome this problem as vitamin D absorbed through the mucosa enters the blood stream directly.

For patients with Cystic Fibrosis that do not normalise vitamin D in their blood by taking specially formulated multivitamins on a daily basis, the additional daily supplementation of vitamin D with a formulation that enables partial absorption through the oral mucosa can help them to achieve normal vitamin D levels.

References: